Group work has many benefits to students and student learning, but it also has its challenges. Most common problems can be avoided if you put in the effort and take the time to plan carefully. One of the early steps to take into consideration as you prepare is how to form groups. There are many decisions to make, and the best option varies based on the objective, the activity, and the duration of the students’ collaboration.

Main Idea

Forming effective groups can be difficult, but it is an important activity as the group’s composition can affect student working relationships and ultimately learning outcomes.

Designing Groups

Groups may be defined by kind, size, or makeup.

Group Kind

Formal, informal, and base groups are all options for group work (Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1991).

- Informal groups are formed rapidly, arbitrarily, and for a small length of time to answer to a question, generate ideas, or engage in another activity that acts as a break from a longer class activity.

- Formal groups are formed to achieve a more difficult objective, such as producing a report or creating a presentation. These groups work together until the task is complete, which might take multiple class sessions or even weeks.

- Base groups are intended to build a community of learners who work on a range of projects over the duration of a term or even an academic year. Due to the long-term nature of these groups, their purpose is to achieve an overarching course objective and provide members with support and encouragement (Johnson et al., 1991).

Consequently, the style of group you choose to use–informal, formal, or base–depends on the work and the amount of time necessary to complete it.

Group Size

Group size typically ranges from two to six students for effective collaborative work. Bean (1996, p. 160) gives a compelling argument for settling on five as the most effective size for formal and informal classroom groups. He notes that six will work almost as well, but that larger groups dilute the experience; groups of four tend to divide into pairs, and groups of three split into a pair and an outsider.

The size of the group therefore depends on the type of group, the nature of the assignment, the duration of the task, and to some extent the physical setting. Collaborative learning proponents generally recommend that the group be small enough so that students can participate fully and build confidence in one another, but large enough to have sufficient diversity and the necessary resources to complete the learning task.

Group Makeup

Groups can be heterogeneous or homogeneous.

In general, research supports heterogeneous grouping because working with diverse students exposes individuals to people with different ideas, backgrounds, and experiences (Johnson et al., 1991). There are, however, disadvantages to heterogeneous groups. Students can be uncomfortable with the diversity of opinion and the potential tension that results from disagreement.

Homogenous grouping has advantages for certain types of learning activities. For instance, students who share common characteristics may feel comfortable enough to discuss or explore highly sensitive or personal issues (Brookfield & Preskill, 1999). Homogenous groups may also master highly structured skill-building tasks more efficiently because students can communicate with each other beginning from a similar level of knowledge.

In the lack of a clear basis for allocating group membership, instructors may opt for random assignment or choose to mix groups over the term so that groups are sometimes homogeneous and sometimes heterogeneous.

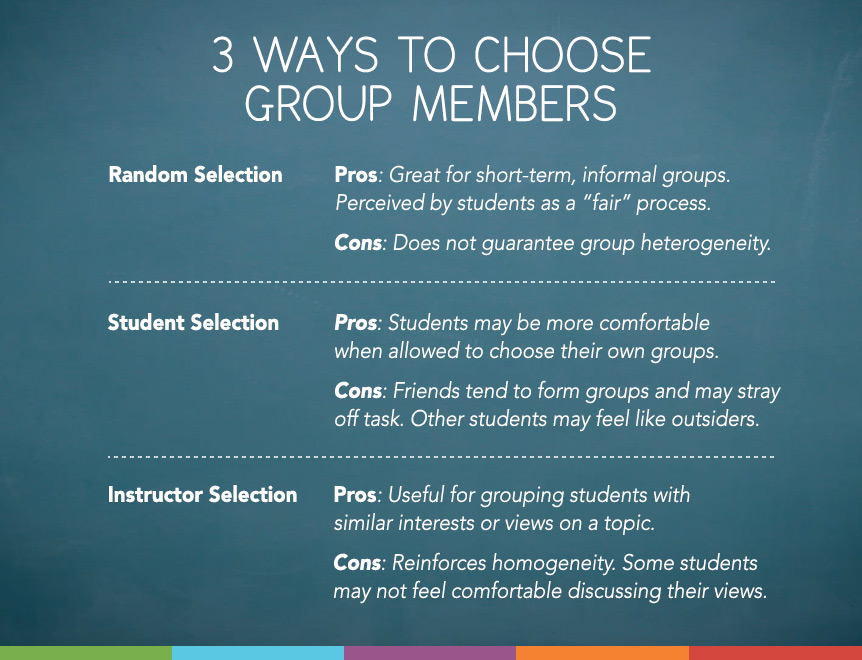

Choosing Group Members

There are essentially three techniques for group membership assignment: random, student selection, and instructor determination.

Random

Random selection is ideal for most informal groups organized for short-term assignments, and it is also useful for breaking up longer-term formal or base groups to create variety. Students perceive this selection process as “fair,” and although random selection does not guarantee heterogeneity, if used frequently, random grouping provides students with opportunities to work with a variety of individuals. This strategy tends to generate homogenous groupings if you point to learners sitting near to each other. Suggestions for forming random groups are:

- Walk up classroom aisles stating “Odd,” “Even,” “Odd,” “Even” for each row, and then urge learners in the “odd” row to turn around and create groups of four to six with those in the “even” row.

- Ask students to count off in class. The first student begins by saying “One,” the second “Two,” and so on, counting up to the desired number of groups and then starting the cycle again. This tends to break up cliques of students sitting together.

- Distribute numbers written on slips of paper or have students select a number from a hat or other container for large courses where a count-off technique could generate confusion due to the number of students.

- Ask students to form a line according to their birthdays (or the alphabetical order of their first and last names, their height, and so forth). Break the line to establish the required number of groups for an activity.

- Find a number of pictures or graphics, rip or cut each one into pieces, and ask students to find others with matching pieces. This strategy works well in geography, art, landscape design, and other courses where visual images are essential.

Example

An English professor wishing to have students form into random-assignment groups used a line from a poem and asked students to group with other members of the class who had lines in the same stanza. This strategy emphasized the recognition of the text passages.

Student Choice

Students may feel more comfortable and be more motivated to work together if they are allowed to choose their partners or group members (Brookfield & Preskill, 1999). However, student choice tends to create groups based on friendships, leaving some students feeling like outsiders and increasing the likelihood that students will stray off task. Ways to structure student choice include:

- Group Leader Selection. Consider providing them with criteria, such as asking them to choose group members who have the most complementary skills to their own, who will provide the most diversity, or with whom they have not previously collaborated.

- Team Hiring. Identify students who will function as “employers.” These students are responsible for identifying the characteristics that will contribute most to the success of their team. Depending on the assignment, these characteristics may include content knowledge, a specific group work skill (such as facilitation, research, or presentation skills), or demographic traits.

Instructor Selection Criteria

Selection can be based on student interests or student characteristics for formal or base groups. Interest grouping is useful for motivating students and assigning roles based on a particular viewpoint, for example for a debate. The disadvantages of interest grouping are that it may reinforce homogeneity and students may not be comfortable having their views on certain topics discussed. If you decide to select groups based on a specific criterion, some options include:

- Student Sign-Up. Choose topics for students to investigate, write them on a sign-up sheet or post them on several signs around the room, and ask students to sign up for their preferences. Either predetermine the number of slots available for each group and allow students to sign up on a first-come, first-served basis, or leave the number of slots undetermined and organize students into groups after everyone has indicated their preference.

- Single-Statement Likert Scale Rating. Prepare a statement that encapsulates an important or controversial issue in the field on which attitudes and opinions will vary. Ask students to select the number on a five-point Likert scale that best describes their position (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree).

- Corners. Designate a type of characteristic or a specific “interest” for each of the four corners of the room. For instance, the corners could represent clusters of academic majors or answers to a multiple-choice question (such as “The greatest value of college life comes from (a) academic subjects studied; (b) social skills acquired; (c) networks formed with peers and professors; and (d) the opportunity to interact with people of differing cultures and backgrounds”).

- Data Sheet. Develop a data sheet that can be distributed with the syllabus to elicit demographic characteristics, skills, or academic information such as expertise in technology, academic major, the number of courses taken in the major, the number of job-related experiences, etc. Use this information to form homogenous or heterogeneous groups.

Depending on the learning activity, the selection method can be changed throughout the term. For instance, random techniques work best for quick formation of informal groups, whereas instructor-determined techniques work better for formal and base groups. Alternatively, elements of different selection techniques can be combined, such as allowing students to identify three classmates with whom they would like to work, and then having you as the instructor make an effort to assign one identified classmate to each group.

What are some group work Cross Academy Techniques for which I can apply different approaches to forming groups?

Many Cross Academy Techniques involve group work, but here are three examples for which careful group formation can be quite important:

In Jigsaw, students work in small groups to develop knowledge about a given topic before teaching what they learned to another group.

A Triple Jump is a three-step technique that requires students to think through and attempt to solve a real-world problem.

With Case Studies, student teams review a real-life problem scenario in depth. Team members apply course concepts to identify and evaluate alternative approaches to solving the problem.

Team Jeopardy is a game in which student teams take turns selecting a squre from a grid that is organized vertically by category and horizontally by difficulty. Each square shows the number of points the team can earn if they answer a question correctly, and more challenging questions have the potential to earn more points. (This technique includes a downloadable set of example slides.)

Key Reference and Resources

Barkley, E. F., Major, C. H. & Cross, K. P. (2014; 2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A resource for college faculty (2nd ed). Jossey-Bass.

Bean, J. C. (2013). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Brame, C.J. & Biel, R. (2015). Setting up and facilitating group work:

Using cooperative learning groups effectively. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/setting-up-and-facilitating-group-work-using-cooperative-learning-groups-effectively/.

Brookfield, S. D., & Preskill, S. (2005). Discussion as a way of teaching: Tools and techniques for democratic classrooms. Jossey-Bass.

Eberly Center. (2022). How can I compose groups? Carnegie Mellon University. https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/compose.html

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1991). Cooperative learning: Increasing college faculty instructional productivity (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports, No. 4). George Washington University. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED343465.pdf

Suggested Citation

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (n.d.). Making group work work: Strategies for forming effective groups. CrossCurrents. https://kpcrossacademy.org/making-group-work-work-strategies-for-forming-effective-groups/

Engaged Teaching

A Handbook for College Faculty

Available now, Engaged Teaching: A Handbook for College Faculty provides college faculty with a dynamic model of what it means to be an engaged teacher and offers practical strategies and techniques for putting the model into practice.